Economics

Economicsis the social

science that analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods

and services. The term economics comes from the Ancient Greek “oikonomia”,

where ‘oikos’means "house" and ` nomos’ means “custom" or "law".

In this sense “oikonomia” means "management of a household, or "rules

of the house"

There are a variety of

modern definitions of economics. Some of the differences may reflect evolving

views of the subject or different views among economists.

Alfred Marshall provides a still widely-cited definition in his textbook

Principles of Economics (1890) that extends analysis beyond wealth and from the

societal to the macroeconomic level:

-----Economics is a study

of man in the ordinary business of life. It enquires how he gets his income and

how he uses it. Thus, it is on the one side, the study of wealth and on the

other and more important side, a part of the study of man.

Lionel Robbins (1932) developed implications of what has been termed "perhaps

the most commonly accepted current definition of the subject".

----Economics is a science

which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means

which have alternative uses.

Lastly we can say that, the theories,

principles, and models that deal with how the market process works. It

attemptsto explain how wealthis created and distributed in communities, how

people allocateresources that are scarce and have many alternative uses, and

other such matters that arise in dealing with human wants and their satisfaction.

Importance/objective

of economic

The Importance /advantages/

Objectives of the study of economics are as under:

(1) Intellectual Value:

The knowledge of Economics

is very useful as it broadens our outlook, sharpens our intellect, and

inculcates in us the habit of balanced thinking. The study of Economics makes

us realize that we as human beings are dependent upon one another for our daily

needs. This feeling creates in us the intelligent appreciation of our position

and the spirit of co-operation with others.

(2) Practical Advantages:

The practical advantages of

Economics are much more important than its theoretical advantages. These

advantages can be looked at from the individual and community point of view.

(3) Personal Stake in Economics:

From personal point of

view, the study of Economics is useful as it enables each of us to understand

better and appreciate more intelligently the nature and significance of our

money earning and money spending activities. With the knowledge of Economics, the

consumer can better adjust his expenditure to his income. The study of

Economics is also useful to a producer. It suggests him the ways of bringing

about the most economical combinations of the various factors of production at

his disposal. It also helps in solving the various intricacies of exchange.

From the study of Economics, one can easily judge as to why the prices have

risen or fallen. The knowledge of Economics also explains us as to how the

reward of various factors of production is determined. Thus, we find that

every’ individual can rightly hope to become a better and more efficient

consumer, producer and businessman, if he has the working knowledge of

economics.

(4) Economics for the Leader:

The study of economics is

not only helpful from the individual point of view but it is also very useful

for the welfare of the community. It enables a statesman to understand and

better grasp the economic and social problems facing the country. Every

government has to tackle different kinds of economic problems such as

unemployment, inflation, over production, under-production, imposition of

tariffs and control, problem of monopolies, etc. the statesman can successfully

solve these problems, if he has thorough knowledge of the subject of Economics.

The knowledge of Economics for a finance minister is also indispensable. He has

to raise revenue by imposing taxes on the incomes of the people for meeting the

necessary expenditure of the government. Economics here comes to his rescue and

guides him as to how the taxes could be levied and collected.

(5) Poverty and Development:

The greatest advantage of

Economics is that it helps in removing traces of poverty from the country. Take

the case of Pakistan; we in Pakistan are confronted with different kinds of problems.

For example, low-per capita income, low productivity of agriculture, slow

development of industries, fast increase in population, under-developed means

of communication and transport, etc. The study of Economics helps in devising

ways and means and suggesting practical measures in solving these problems.

(6) Economics for the citizen:

Such being, the importance

of study of Economics, it is rightly remarked by Wooten that “you cannot be in

real sense a citizen unless you are also in some degree an economist”. He is

perfectly right in giving the statement. The world is so fast changing that we

are completely now living in a world dominated by economic forces and economic

ideas. If the people of any country do not have the working knowledge of an economic

system; then the government of that country can easily hoodwink citizens have

knowledge of Economics, then the government will be very vigilant and spend the

money in a wise manner.

The importance of the study

of Economies can also be judged from this fact that the daily newspapers cannot

be understood without some knowledge of Economics. The newspapers often

describe complicated economic problems such as inflation, balance of payment,

balance of trade, imperfect markets, dumping, co-operative farming,

sub-division and fragmentation of holdings, mechanization of agriculture, If

you do not have working knowledge of Economics, you cannot understand these

diverse problems.

From brief discussion, we conclude, that the knowledge of Economics is very useful. As such it is necessary that every citizen, worker, administrator, consumer, etc., should have at least working knowledge of it. In the words of Sir Henry Clay:

“Some study of Economics is at one a

practical necessity and a normal obligation”.

Production: Production is the conversion of input into

output. The factors of production and all other things which the producer buys

to carry out production are called input. The goods and services produced are

known as output. Thus production is the activity that creates or adds utility

and value. In the words of Fraser, "If consuming means extracting utility

from matter, producing means creating utility into matter". According to

Edwood Buffa,

“Production is a process by which goods and

services are created"

What are the Factors of Production? As already stated, production is a process of

transformation of factors of production (input) into goods and services

(output). The factors of production may be defined as resources which help the

firms to produce goods or services. In other words, the resources required to

produce a given product are called factors of production. Production is done by

combining the various factors of production. Land, labor, capital and

organization (or entrepreneurship) is the factors of production (according to

Marshall).

We can use the word CELL to help us remember

the four factors of production: C- capital; E-Entrepreneurship; L- land: and L-

labor.

1. The ownership of the

factors of production is vested in the households.

2. There is a basic

distinction between factors of production and factor services. It is these

factor services, which are combined in the process of production.

3. The different units of a

factor of production are not homogeneous. For example, different plots of land

have different level of fertility. Similarly laborers’differ in efficiency.

4. Factors of production

are complementary. This means their co-operation or combination is necessary

for production.

5. There is some degree of substitutability

between factors of production. For example, labour can be substituted for

capital to a certain extent.

The firm is an organization

that combines and organizes labor, capital and land or raw materials for the

purpose of producing goods and services for sale. The aim of the firm is to

maximize total profits or achieve some other related aim, such as maximizing

sales or growth. The basic production decision facing the firm is how much of

the commodity or services to produce and how much labor, capital and other

resources or inputs to use to produce that output most efficiently. To answer

these questions, the firm requires engineering or technological data on

production possibilities (the so called production function) as well as

economic data on input and output prices.

Production refers to the

transformation of inputs or resources into outputs of goods and services. For

example: IBM hires workers to use machinery, parts and raw materials in

factories to produce personal computers. The output of a firm can either be a

final commodity (such as personal computer) or an intermediate product such as

semiconductors (which are used in the production of computers and other goods).

The output can also be a service rather than a good. Examples of services are

education, medicine, banking, communication, transportation and many others. To

be noted is, that production refers to all of the activities involved in the

production of goods and services, from borrowing to set up or expand production

facilities, to hiring workers, purchasing raw materials, running quality

control, cost accounting and so on, rather than referring merely to the

physical transformation of inputs into outputs of goods and services.

Inputs are the resources

used in the production of goods and services. As a convenient way to organize

the discussion, inputs are classified into labor. (Including entrepreneurial

talent), capital and land or natural resources. Each of these broad categories

however includes a great variety of the basic input. For example, labor

includes bus drivers, assembly line workers, accountants, lawyers, doctor’s

scientists and many others. Inputs are also classified as fixed or variable.

Fixed inputs are those that cannot be readily changed during the time period

under consideration, except at very great expense. Examples of fixed inputs are

the firm's plant and specialized equipment. On the other land, variable inputs

are those that can be varied easily and on the very short notice. Examples of

variable inputs are most raw materials and unskilled labor.

The time period during which at least one

input is fixed is called the short run, while the time period when all inputs

are variable is called the long run. The length of the long run depends on the

industry. For some, such as the setting up or expansion of a dry cleaning

business, the long run may be only few months or weeks. For others, much as the

construction of new electricity, generating plant, it may be many years. In the

short run, a firm can increase output only by using more of the variable inputs

together with the fixed inputs. In the long run, the same increase in output

could very likely be obtained more efficiently by also expanding the firm's

production facilities. Thus we say that the firm operates in the short run and

plans increases or reductions in its scale of operation in the long run. In the

long run, technology usually improves, so that more output can be obtained from

a given quantity of inputs or the same output from less input.

Production is the process

by which inputs are transformed in to outputs. Thus there is relation between

input and output. The functional relationship between input and output is known

as production function. The production function states the maximum quantity of

output which can be produced from any selected combination of inputs. In other

words, it states the minimum quantities of input that are necessary to produce

a given quantity of output.

The production function is

largely determined by the level of technology. The production function varies

with the changes in technology. Whenever technology improves, a new production

function comes into existence. Therefore, in the modern times the output

depends not only on traditional factors of production but also on the level of

technology.

The production function can

be expressed in an equation in which the output is the dependent variable and

inputs are the independent variables. The equation is expressed as follows:

Q= f (L, K, T……………n)

Where,

Q = output

L = labour

K = capital

T = level of technology

n = other inputs employed

in production.

There are two types of

production function - short run production function and long run production

function. In the short run production function the quantity of only one input

varies while all other inputs remain constant. In the long run production

function all inputs are variable.

Assumptions of Production

Function

The production function is

based on the following assumptions.

1. The level of technology

remains constant.

2. The firm uses its inputs

at maximum level of efficiency.

3. It relates to a

particular unit of time.

4. A change in any of the

variable factors produces a corresponding change in the output.

5. The inputs are divisible into most viable

units.

The production function is

of great help to a manager or business economist. The managerial uses of

production function are outlined as below:

1. It helps to determine

least cost factor combination: The production function

is a guide to the entrepreneur to determine the least cost factor combination.

Profit can be maximized only by minimizing the cost of production. In order to

minimize the cost of production, inputs are to be substituted. The production

function helps in substituting the inputs.

2. It helps to determine

optimum level of output: The production function

helps to determine the optimum level of output from a given quantity of input.

In other words, it helps to arrive at the producer's equilibrium.

3. It enables to plan the

production: The production function helps the

entrepreneur (or management) to plan the production.

4. It helps in decision-making: Production function is very useful to the management to take decisions

regarding cost and output. It also helps in cost control and cost reduction. In

short, production function helps both in the short run and long run

decision-making process.

Define Inflation: Inflation can be defined as a sustained or

continuous rise in the general price level or, alternatively, as a sustained or

continuous fall in the value of money.

Several things should be noted about this

definition. First, inflation refers to the movement in the general level of

prices. It does not refer to changes in one price relative to other prices.

These changes are common even when the overall level of prices is stable and

the rise in the price level must be somewhat substantial and continue over a

period longer than a day, week, or month.

Economists wake up in the

morning hoping for a chance to debate the causes of inflation. There is no one

cause that's universally agreed upon, but at least two theories are generally

accepted:

Demand-Pull Inflation

This theory can be

summarized as "too much money chasing too few goods". In other words,

if demand is growing faster than supply, prices will increase. This usually

occurs in growing economies.

Cost-Push Inflation

When companies' costs go up, they need to

increase prices to maintain their profit margins. Increased costs can include

things such as wages, taxes, or increased costs of imports.

Almost everyone thinks

inflation is evil, but it isn't necessarily so. Inflation affects different

people in different ways. It also depends on whether inflation is anticipated

or unanticipated. If the inflation rate corresponds to what the majority of

people are expecting (anticipated inflation), then we can compensate and the

cost isn't high. For example, banks can vary their interest rates and workers

can negotiate contracts that include automatic wage hikes as the price level

goes up.

Costs/ affects arise when there is unanticipated inflation:

1.

Creditors lose and debtors gain if the lender does not anticipate inflation

correctly. For those who borrow, this is similar to getting an interest-free

loan.

2.

Uncertainty about what will happen next makes corporations and consumers less

likely to spend. This hurts economic output in the long run.

3.

People living off a fixed-income, such as retirees, see a decline in their

purchasing power and, consequently, their standard of living.

4.

The entire economy must absorb repricing costs ("menu costs") as

price lists, labels, menus and more have to be updated.

5.

If the inflation rate is greater than that of other countries, domestic

products become less competitive.

People often complain about

prices going up, but they often ignore the fact that wages should be rising as

well. The question shouldn't be whether inflation is rising, but whether it's

rising at a quicker pace than your wages.

Lastly,

inflation is a sign that an economy is growing. In some situations, little

inflation (or even deflation) can be just as bad as high inflation. The lack of

inflation may be an indication that the economy is weakening. As you can see,

it's not so easy to label inflation as either good or bad - it depends on the

overall economy as well as your personal situation.

Money is any good that is

widely used and accepted in transactions involving the transfer of goods and

services from one person to another. Economists differentiate among three

different types of money: commodity money, fiat money, and bank money.

The functions of money

The function of money can be categorized in two classes. These

are-

A. Primary or main function

B. secondary or Supporting function

Primary or main function

Money is often defined in

terms of the four functions or services that it provides. Money serves as a

medium of exchange, as a Measure of Value, Standard of Deferred Payments and as

Store of Value.

1.

Medium of Exchange:

The most important function

of money is to serve as a medium of exchange or as a means of payment. To be a

successful medium of exchange, money must be commonly accepted by people in

exchange for goods and services. While functioning as a medium of exchange,

money benefits the society in a number of ways:

(a) It overcomes the

inconvenience of baiter system (i.e., the need for double coincidence of wants)

by splitting the act of barter into two acts of exchange, i.e., sales and

purchases through money.

(b) It promotes

transactional efficiency in exchange by facilitating the multiple exchange of

goods and services with minimum effort and time,

(c) It promotes allocation

efficiency by facilitating specialization in production and trade,

(d) It allows freedom of

choice in the sense that a person can use his money to buy the things he wants

most, from the people who offer the best bargain and at a time he considers the

most advantageous.

2.

Measure of Value:

Money serves as a common

measure of value in terms of which the value of all goods and services is measured

and expressed. By acting as a common denominator or numeraire, money has

provided a language of economic communication. It has made transactions easy

and simplified the problem of measuring and comparing the prices of goods and

services in the market. Prices are but values expressed in terms of money.

Money also acts as a unit

of account. As a unit of account, it helps in developing an efficient

accounting system because the values of a variety of goods and services which

are physically measured in different units (e.g, quintals, metres, litres,

etc.) can be added up. This makes possible the comparisons of various kinds,

both over time and across regions. It provides a basis for keeping accounts,

estimating national income, cost of a project, sale proceeds, profit and loss

of a firm, etc.

To be satisfactory measure

of value, the monetary units must be invariable. In other words, it must

maintain a stable value. A fluctuating monetary unit creates a number of

socio-economic problems. Normally, the value of money, i.e., its

purchasing power, does not remain constant; it rises during periods of falling

prices and falls during periods of rising prices.

3.

Standard of Deferred Payments:

When money is generally

accepted as a medium of exchange and a unit of value, it naturally becomes the

unit in terms of which deferred or future payments are stated.

Thus, money not only helps

current transactions though functions as a medium of exchange, but facilitates

credit transaction (i.e., exchanging present goods on credit) through its

function as a standard of deferred payments. But, to become a satisfactory

standard of deferred payments, money must maintain a constant value through

time ; if its value increases through time (i.e., during the period of falling

price level), it will benefit the creditors at the cost of debtors; if its

value falls (i.e., during the period of rising price level), it will benefit

the debtors at the cost of creditors.

4.

Store of Value:

Money, being a unit of

value and a generally acceptable means of payment, provides a liquid store of

value because it is so easy to spend and so easy to store. By acting as a store

of value, money provides security to the individuals to meet unpredictable

emergencies and to pay debts that are fixed in terms of money. It also provides

assurance that attractive future buying opportunities can be exploited.

Money as a liquid store of

value facilitates its possessor to purchase any other asset at any time. It was

Keynes who first fully realised the liquid store value of money function and

regarded money as a link between the present and the future. This, however,

does not mean that money is the most satisfactory liquid store of value. To

become a satisfactory store of value, money must have a stable value.

Secondary or Supporting

function

1.

Transfer of Value:

Money also functions as a

means of transferring value. Through money, value can be easily and quickly

transferred from one place to another because money is acceptable everywhere

and to all. For example, it is much easier to transfer one lakh rupees through

bank draft from person A in Amritsar to person B in Bombay than remitting the

same value in commodity terms, say wheat.

2.

Distribution of National Income:

Money facilitates the

division of national income between people. Total output of the country is

jointly produced by a number of people as workers, land owners, capitalists,

and entrepreneurs, and, in turn, will have to be distributed among them. Money

helps in the distribution of national product through the system of wage, rent,

interest and profit.

3.

Maximization of Satisfaction:

Money helps consumers and

producers to maximize their benefits. A consumer maximizes his satisfaction by

equating the prices of each commodity (expressed in terms of money) with its

marginal utility. Similarly, a producer maximizes his profit by equating the

marginal productivity of a factor unit to its price.

4.

Basis of Credit System:

Credit plays an important

role in the modern economic system and money constitutes the basis of credit.

People deposit their money (saving) in the banks and on the basis of these

deposits, the banks create credit.

5.

Liquidity to Wealth:

Money imparts liquidity to various forms of

wealth. When a person holds wealth in the form of money, he makes it liquid. In

fact, all forms of wealth (e.g., land, machinery, stocks, stores, etc.) can be

converted into money.

Unemployment occurs when

people are without work and actively seeking work.

According to the ILO

guidelines, a person is unemployed if the person is (a) not working, (b)

Currently available for work and (c) seeking work. Here a person is to be

considered unemployed if he/she during the reference period simultaneously

satisfies being:

(a)‘Without work’, i.e.,

were not in paid employment or self-employment as specified by the

international definition

(b)‘Currently available for

work’, i.e., were available for paid employment or self-employment during the

reference period; and

(c)‘Seeking work’, i.e.,

had taken specific steps in a specified recent period to seek paid employment

or self-employment.

In the words of Fairchild,

“unemployment is forced and involuntary separation from remunerative work on

the part of the normal wages and normal conditions.”

According to Sergeant

Florence, “unemployment has been defined as the idleness of persons able to

work.”

Lastly we can say that When a person is

failed to get any job and unable to found the means of livelihood, we call him

an unemployed person. Thus, unemployment means lack of absence of employment.

In other word unemployment is largely concerned with those persons who

constitute the labor force of the country, who are able bodied and willing to

work, but they are gainfully employed. Unemployment, therefore, is the lack of

earning or idleness on the part of a person who is able to work.

As unemployment is a

universal problem and is found in every country more or less, therefore, it is

categorised into a number of types. The chief among them are stated below:

1) Structural unemployment:

Basically Bangladesh's

unemployment is structural in nature. It is associated with the inadequacy of

productive capacity to create enough jobs for all those able and willing to

work. In Bangladesh not only the productive capacity much below the needed

quantity, it is also found increasing at a slow rate. As against this, addition

to labour force is being made at a first rate on account of the rapidly growing

population. Thus, while new productive jobs are on the increase, the rate of

increasing being low the absolute number of unemployed persons is rising from

year to year.

2) Disguised unemployment:

Disguised unemployment

implies that many workers are engaged in productive work. For example, in

Indian villages, where most of unemployment exists in this form, people are

found to be apparently engaged in agricultural works. But such employment is

mostly a work sharing device i.e., the existing work is shared by the large

number of workers. In such a situation, even if many workers are withdrawn, the

same work will continue to be done by fewer people.

It follows that all the

workers arte not needed to maintain the existing level of production. The

contribution of such workers to production is nothing. It is found that the

very large numbers of workers on Indian farms actually hinder agricultural

works and thereby reduce production.

3) Cyclical unemployment:

Cyclical unemployment in

caused by the trade or business cycles. It results from the profits and loss

and fluctuations in the deficiency of effective demand production is slowed

down and there is a general state of depression which causes unemployment

periods of cyclical unemployment is longer and it generally affects all

industries to a greater or smaller extent.

4) Seasonal unemployment:

Seasonal unemployment

occurs at certain seasons of the year. It is a widespread phenomenon of Indian

villages basically associated with agriculture. Since agricultural work depends

upon Nature, therefore, in a certain period of the year there is heavy work,

while in the rest, the work is lean. For example, in the sowing and harvesting

period, the agriculturists may to engage themselves day and night.

But the period between the

post harvest and pre sowing is almost workless, rendering many without work.

Thus, seasonal unemployment is largely visible after the end of agricultural

works.

5) Underemployment:

Underemployment usually

refers to that state in which the self employed working people are not working

according to their capacity. For example, a diploma holder in engineering, if

for wants of an appropriate job, start any business may be said to be

underemployed. Apparently, he may be deemed as working and earning in a

productive activity and in this sense contributing something to production.

But in reality he is not

working to his capability, or to his full capacity. He is, therefore, not full

employed. This type of unemployment is mostly visible in urban areas.

6) Open Unemployment:

Open unemployment is a

condition in which people have no work to do. They are able to work and are

also willing to work but there is no work for them. They are found partly in

villages, but very largely in cities. Most of them come form villages in search

of jobs, many originate in cities themselves. Such employment can be seen and

counted in terms of the number of such persons.

Hence it is called upon

unemployment. Open unemployment is to be distinguished from disguised

unemployment and underemployment in that while in the case of former

unemployment workers are totally idle, but in the latter two types of

unemployment they appear to be working and do not seem to be away their time.

7) Voluntary Unemployment:

Voluntary unemployment

occurs when a working persons willingly withdraws himself from work. This type

of unemployment may be caused due to a number of reasons. For example, one may

quarrel with the employer and resign or one may have permanent source of

unearned income, absentee workers, and strikers and so on. In voluntary

unemployment, a person is out of job of his own desire. She does not work on

the prevalent or prescribed wages. Either he wants higher wages or does not

want to work at all.

8) Involuntary

unemployment:

Involuntary unemployment occurs when at a

particular time the number of worker is more than the number of jobs. Obviously

this state of affairs arises because of the insufficiency or non availability

of work. It is customary to characterise involuntary unemployment, not

voluntary as unemployment proper.

Ways and means to remove

unemployment in Society of Bangladesh removal of unemployment is the

responsibility of the state. The Constitutional of Bangladesh has the

“Directive Principles” of the State and enjoined this duty on the State

Government.

In Society we have already

seen that there is a good deal of unemployment. This removal of unemployment is

necessary for the prosperity of the nation. For this, the following steps have

to be taken:

1) Improvement in the

agricultural system:

We have already seen that

the agricultural system in Bangladesh is backward and underdeveloped. This

backwardness is responsible for a lot of unemployment. If the unemployment has

to removed, the system of agriculture has to be modernized and improved, for

this the following steps to be taken:

1) Holding should be consolidated and made

economic.

2)Methods of agriculture should be improved and

as far as possible farmers should be freed from dependence on nature.

3) System of crops should be planned

scientifically and improved. If more crops earned they would provide more

employment.

4) The farmers should be provided with good

seed, good fertilizer, healthy animals, modern implements and tools etc.

2) Adequate arrangement of

facilities of irrigation:

In villages the agriculture

very much depends on nature. If rains fail, the crops are destroyed. This

brings about a good deal of unemployment. Methods of irrigation should be made

more modern. They should also be adequate so that it may be possible for people

to water their fields.

3) Increasing the area of

cultivable land:

To day in the villages

there is a great pressure on land. The area under cultivation is not sufficient

to provide food to all the people of this country. Barren land should be broken

and made fertile. Other methods should also be made for improving the area of

cultivable land which is not normally fit for agriculture, also be improved and

made fit. This would remove unemployment in the villages.

4) Setting up and develop

the cottage and village industries:

In village, people have

seasonal employment in agriculture. Apart from it all the persons do not have

avenues for the employment. What is needed is to set up of industries so that

those who do not have land are employed in it. Apart from it, the

agriculturalists during dull season should get employment in these industries.

Women and land less laborers shall also be able to get employment if industries

are set up.

5) Improving the means of

transport and communication:

In villages there is need

to have proper roads and places where offices and stores for seeds etc, may be

set up. Public construction should be undertaken in the villages to provide

employment to the idle hands. This would improve the employment position in the

village. Apart from it, it would also add to the prosperity of the villages.

6) Construction of public

Transports, Roads etc:

It is necessary to improve

the means of transport and communication. This would have two fold advantages.

Firstly, the village people shall be able to send their products to markets for

sale and secondly, they shall also be able to go to such other places where

they can get employment. Apart from it, this would also provide employment to

many persons who shall engage themselves in the task of transporting these

people.

7) Organization of the

agricultural market:

There is need to organize

markets for the agricultural product. At present, there is dearth of such

market. This situation creates difficulties for the agriculturalists. On the one

hand, they are not able to get proper price and on the other hand they have to

suffer from other handicaps. If markets are organized, they would provide

employment to certain hands and also help the agriculturalists to get proper

price for their labor.

In fact Bangladesh is such a vast country and

unemployment is so large that “Herculean” efforts shall have to be made to

surmount this degree. Various economists and social thinkers have suggested

various ways for it. Many of these ways have also been incorporated in the Five

Year Plans. In spite of these Five Year Plans employment position is far from

satisfactory.

There are three main

factors that influence a demand’s price elasticity:

1. The availability of

substitutes

This is probably the most

important factor influencing the elasticity of a good or service. In general,

the more substitutes, the more elastic the demand will be. For example, if the

price of a cup of coffee went up by $0.25, consumers could replace their

morning caffeine with a cup of tea. This means that coffee is an elastic good

because a raise in price will cause a large decrease in demand as consumers start

buying more tea instead of coffee.

However, if the price of

caffeine were to go up as a whole, we would probably see little change in the

consumption of coffee or tea because there are few substitutes for caffeine.

Most people are not willing to give up their morning cup of caffeine no matter

what the price. We would, therefore, say that caffeine is an inelastic product

because of its lack of substitutes. Thus, while a product within an industry is

elastic due to the availability of substitutes, the industry itself tends to be

inelastic. Usually, unique goods such as diamonds are inelastic because they

have few - if any - substitutes.

2. Amount of income

available to spend on the good

This factor affecting

demand elasticity refers to the total a person can spend on a particular good

or service. Thus, if the price of a can of Coke goes up from $0.50 to $1 and

income stays the same, the income that is available to spend on Coke, which is

$2, is now enough for only two rather than four cans of Coke. In other words,

the consumer is forced to reduce his or her demand of Coke. Thus if there is an

increase in price and no change in the amount of income available to spend on

the good, there will be an elastic reaction in demand: demand will be sensitive

to a change in price if there is no change in income.

3. Time

The third influential factor is time. If the

price of cigarettes goes up $2 per pack, a smoker, with very little available

substitutes, will most likely continue buying his or her daily cigarettes. This

means that tobacco is inelastic because the change in the quantity demand will

have been minor with a change in price. However, if that smoker finds that he

or she cannot afford to spend the extra $2 per day and begins to kick the habit

over a period of time, the price elasticity of cigarettes for that consumer

becomes elastic in the long run.

Sometimes a country or an individual can

produce more than another country, even though countries both have the same

amount of inputs. For example, Country A may have a technological advantage

that, with the same amount of inputs (arable land, steel, labor), enables the

country to manufacture more of both cars and cotton than Country B. A country

that can produce more of both goods is said to have an absolute advantage.

Better quality resources can give a country an absolute advantage as can a

higher level of education and overall technological advancement. It is not

possible, however, for a country to have a comparative advantage in everything

that it produces, so it will always be able to benefit from trade.

An economy can focus on

producing all of the goods and services it needs to function, but this may lead

to an inefficient allocation of resources and hinder future growth. By using

specialization, a country can concentrate on the production of one thing that

it can do best, rather than dividing up its resources. For example, let's look

at a hypothetical world that has only two countries (Country A and Country B)

and two products (cars and cotton).

Each country can make cars

and/or cotton. Now suppose that Country A has very little fertile land and an

abundance of steel for car production. Country B, on the other hand, has an

abundance of fertile land but very little steel. If Country A were to try to

produce both cars and cotton, it would need to divide up its resources. Because

it requires a lot of effort to produce cotton by irrigating the land, Country A

would have to sacrifice producing cars. The opportunity cost of producing both

cars and cotton is high for Country A, which will have to give up a lot of

capital in order to produce both.

Similarly, for Country B,

the opportunity cost of producing both products is high because the effort

required to produce cars is greater than that of producing cotton. Each country

can produce one of the products more efficiently (at a lower cost) than the

other. Country A, which has an abundance of steel, would need to give up more

cars than Country B would to produce the same amount of cotton. Country B would

need to give up more cotton than Country A to produce the same amount of cars.

Therefore, County A has a comparative advantage over Country B in the

production of cars, and Country B has a comparative advantage over Country A in

the production of cotton.

Now let's say that both

countries (A and B) specialize in producing the goods with which they have a

comparative advantage. If they trade the goods that they produce for other

goods in which they don't have a comparative advantage, both countries will be

able to enjoy both products at a lower opportunity cost.

Furthermore, each country will be exchanging

the best product it can make for another good or service that is the best that

the other country can produce. Specialization and trade also works when several

different countries are involved. For example, if Country C specializes in the

production of corn, it can trade its corn for cars from Country A and cotton

from Country B. Determining how countries exchange goods produced by a

comparative advantage ("the best for the best") is the backbone of

international trade theory. This method of exchange is considered an optimal

allocation of resources, whereby economies, in theory, will no longer be

lacking anything that they need. Like opportunity cost, specialization and

comparative advantage also apply to the way in which individuals interact

within an economy.

Some earlier economists

defined Economics as follows:

According to Adam Smith-

“Economics is an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of the

nations.’’

According to J.B. Say-“Economics

is a science which deals with wealth"

In the above definition

wealth becomes the main focus of the study of Economics. The definition of

Economics, as science of wealth, had some merits. The important ones are:

(i) It highlighted an

important problem faced by each and every nation of the world, namely creation

of wealth.

(ii) Since the problems of

poverty, unemployment etc. can be solved to a greater extent when wealth is

produced and is distributed equitably; it goes to the credit of Adam Smith and

his followers to have addressed to the problems of economic growth and increase

in the production of wealth.

The study of Economics as a

'Science of Wealth' has been criticized on several grounds. The main criticisms

leveled against this definition are;

(i) Adam Smith and other

classical economists concentrated only on material wealth. They totally ignored

creation of immaterial wealth like services of doctors, chartered accountants

etc.

(ii) The advocates of Economics as 'science

of wealth' concentrated too much on the production of wealth and ignored social

welfare. This makes their definition incomplete and inadequate. So it is very

critical to say that economics is a science of wealth or not.

i) Economics is a Positive

Science:

As stated above, Economics

is a science. But the question arises whether it is a positive science or a

normative science. A positive or pure science analyses cause and effect

relationship between variables but it does not pass value judgment. In other

words, it states what is and not what ought to be. Professor Robbins emphasized

the positive aspects of science but Marshall and Pigou have considered the

ethical aspects of science which obviously are normative.

According to Robbins,

Economics is concerned only with the study of the economic decisions of

individuals and the society as positive facts but not with the ethics of these

decisions. Economics should be neutral between ends. It is not for economists

to pass value judgments and make pronouncements on the goodness or otherwise of

human decisions. An individual with a limited amount of money may use it for

buying liquor and not milk, but that is entirely his business. A community may

use its limited resources for making guns rather than butter, but it is no

concern of the economists to condemn or appreciate this policy. Economics only

studies facts and makes generalizations from them. It is a pure and positive

science, which excludes from its scope the normative aspect of human behavior.

Complete neutrality between

ends is, however, neither feasible nor desirable. It is because in many matters

the economist has to suggest measures for achieving certain socially desirable

ends. For example, when he suggests the adoption of certain policies for

increasing employment and raising the rates of wages, he is making value

judgments; or that the exploitation of labour and the state of unemployment are

bad and steps should be taken to remove them. Similarly, when he states that

the limited resources of the economy should not be used in the way they are

being used and should be used in a different way; that the choice between ends

is wrong and should be altered, etc. he is making value judgments.

(ii) Economics is a

Normative Science:

As normative science,

Economics involves value judgments. It is prescriptive in nature and described

'what should be the things'. For example, the questions like what should be the

level of national income, what should be the wage rate, how the fruits of national

product be distributed among people - all fall within the scope of normative

science. Thus, normative economics is concerned with welfare propositions.

Some economists are of the view that value

judgments by different individuals will be different and thus for deriving laws

or theories, it should not be used.

Under this, we generally

discuss whether Economics is science or art or both and if it is a science

whether it is a positive science or a normative science or both. Often a

question arises - whether Economics is a science or an art or both.

(a) Economics is as science:

A subject is considered

science if

->It is a systematized

body of knowledge which studies the relationship between cause and effect.

It is capable of

measurement.

It has its own

methodological apparatus.

It should have the ability

to forecast.

If we analyse Economics, we

find that it has all the features of science. Like science it studies cause and

effect relationship between economic phenomena. To understand, let us take the

law of demand. It explains the cause and effect relationship between price and

demand for a commodity. It says, given other things constant, as price rises,

the demand for a commodity falls and vice versa. Here the cause is price and

the effect is fall in quantity demanded. Similarly like science it is capable

of being measured, the measurement is in terms of money. It has its own

methodology of study (induction and deduction) and it forecasts the future

market condition with the help of various statistical and non-statistical

tools.

But it is to be noted that

Economics is not a perfect science. This is because Economists do not have

uniform opinion about a particular event.

The subject matter of

Economics is the economic behavior of man which is highly unpredictable. Money

which is used to measure outcomes in Economics is itself a dependent variable.

It is not possible to make correct predictions about the behavior of economic

variables.

(b) Economics is as an art:

Art is nothing but practice

of knowledge. Whereas science teaches us to know art teaches us to do. Unlike

science which is theoretical, art is practical. If we analyse Economics, we

find that it has the features of an art also. Its various branches,

consumption, production, public finance, etc. provide practical solutions to

various economic problems. It helps in solving various economic problems which

we face in our day-to-day life.

Thus, Economics is both a science and an art.

It is science in its methodology and art in its application. Study of

unemployment problem is science but framing suitable policies for reducing the

extent of unemployment is an art.

Although the fundamental

economic problem of scarcity in relation to needs is undisputed it would not be

proper to think that economic resources - physical, human, financial are fixed

and cannot be increased by human ingenuity, exploration, exploitation and

development. A modern and somewhat modified definition is as follows:

"Economics is the

study of how men and society choose, with or without the use of money, to

employ scarce productive resources which could have alternative uses, to

produce various commodities over time and distribute them for consumption now

and in the future amongst various people and groups of society".

-Paul A. Samuelson

The above definition is very comprehensive

because it does not restrict to material well-being or money measure as a

limiting factor. But it considers economic growth over time.

Robbinsgave a more scientific definition of Economics. His definition is

as follows:

"Economics is the

science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce

means which have alternative uses".

Strengths of Robbins

Definitions

The definition deals with

the following four aspects:

(i) Economics is a science:

Economics studies economic human behavior

scientifically. It studies how humans try to optimize (maximize or minimize)

certain objective under given constraints. For example, it studies how

consumers, with given income and prices of the commodities, try to maximize

their satisfaction.

(ii) Unlimited ends: Ends refer to wants. Human wants are unlimited. When one want is

satisfied, other wants crop up. If man's wants were limited, then there would

be no economic problem.

(iii) Scarce means: Means refer to resources. Since resources (natural productive

resources, man-made capital goods, consumer goods, money and time etc.) are

limited economic problem arises. If the resources were unlimited, people would

be able to satisfy all their wants and there would be no problem.

(iv) Alternative uses: Not only resources are scarce, they have alternative uses. For

example, coal can be used as a fuel for the production of industrial goods, it

can be used for running trains, it can also be used for domestic cooking purposes

and for so many purposes. Similarly, financial resources can be used for many

purposes. The man or society has, therefore, to choose the uses for which

resources would be used. If there was only a single use of the resource then

the economic problem would not arise.

It follows from the

definition of Robbins that Economics is a science of choice. An important thing

about Robbin's definition is that it does not distinguish between material and

non-material, between welfare and non-welfare. Anything which satisfies the

wants of the people would be studied in Economics. Even if a good is harmful to

a person it would be studied in Economics if it satisfies his wants.

Criticism of Robbins

Definition:

No doubt, Robbins has made

Economics a scientific study and his definition has become popular among some

economists. But his definition has also been criticized on several grounds.

Important ones are:

(i)Robbins has made

Economics quite impersonal and colorless. By making it a complete positive

science and excluding normative aspects he has narrowed down its scope.

(ii)Robbins' definition is

totally silent about certain macro-economic aspects such as determination of

national income and employment.

(iii)His definition does not cover the theory

of economic growth and development. While Robbins takes resources as given and

talks about their allocation, it is totally silent about the measures to be

taken to raise these resources i.e. national income and wealth.

Some economists defined

Economics as a material well-being. Under this group of definitions the

emphasis is on welfare as compared with wealth in the earlier group. Two

important definitions are as follows:

"Economics is a study

of mankind in the ordinary business of life. It examines that part of

individual and social action which is most closely connected with the

attainment and with the use of the material requisites of well-being. Thus, it

is on the one side a study of wealth and on the other and more important side a

part of the study of the man",

-Alfred Marshall

"The range of our

inquiry becomes restricted to that part of social welfare that can be brought

directly or indirectly into relation with the measuring rod of money"

-A.C. Pigou.

In the first definition

Economics has been indicated to be a study of mankind in the ordinary business

of life. By ordinary business we mean those activities which occupy

considerable part of human effort. The fulfillment of economic needs is a very

important business which every man ordinarily does. Professor Marshall has

clearly pointed that Economics is the study of wealth but more important is the

study of man. Thus, man gets precedence over wealth. There is also emphasis on

material requisites of well-being. Obviously, the material things like food,

clothing and shelter, are very important economic objectives.

The second definition by

Pigou emphasizes social welfare but only that part of it which can be related

with the measuring rod of money. Money is general measure of purchasing power

by the use of which the science of Economics can be rendered more precise.

Marshall's and Pigou's

definitions of Economics are wider and more comprehensive as they take into

account the aspect of social welfare. But their definitions have their share of

criticism. Their definitions are criticized on the following grounds.

(i)Economics is concerned

with not only material things but also with immaterial things like services of

singers, teachers, actors etc. Marshall and Pigou chose to ignore them.

(ii)Robbins criticized the welfare definition

on the ground that it is very difficult to state which things would lead to

welfare and which will not. He is of the view that we would study in Economics

all those goods and services which carry a price whether they promote welfare

or not.

Monopoly

One firm

Complete barrier to entry

Total control over price

One product

Oligopoly

2-3 firms

High barrier to entry

Control majority of output

Similar/identical products

Monopolistic Competition

Many Firms

Few artificial barriers to

entry

Slight control over price

Differentiated products

Perfect (Pure) Competition

Many Buyers and Sellers

Identical Products

Informed Buyers and Sellers

Free Market Entry and Exit

Consumer Income

Income goes up; consumers

will buy more shifting demand to the right. Goes down, consumers will buy less

shifting demand to the left.

Consumer Expectations

If consumers think prices, for economy,

technology, etc., will change in the future this will have an effect on their

consumption of today.

Population

Population increases the number of consumers

and can shift demand to the right. Decreases shift to the left.

Consumer Tastes and Advertising

Consumer’s change over time the things that

they want. As they change their tastes, their demand shifts to the right or the

left.

Price of Related Goods

Complementary and Substitute items can have

an effect on what consumers will purchase and increase the demand for products.

Effects of Rising Costs

Input costs can have a major effect on the

production and supply of goods and services. Gas prices can limit the services

of a landscaper or paper delivery person.

Technology

Increases in the ability to

produce because of technological advances can shift the supply curve to the

right. Breakdowns in technology can shift it to the left.

Subsidies

Government payments to

firms can act as an incentive to produce more, which can affect supply. If

government removes subsidies the curve will shift left.

Taxes

Government taxation towards

firms can act as an incentive to produce, which can affect supply. If

government removes taxes the curve will shift left, increases shift right.

Future Expectations

How suppliers view the

future of the economy will affect their production of inventory today. If they

think the economy is strong they will increase production today and Vice versa.

Number of Suppliers

Firms increase whenever their profit is to be

made. They decrease whenever profit is reduced. Both will shift the curve to

the right or the left.

There are various concepts of

national income

Gross National Product

(GNP)

Gross national product is

defined as the total market value of all final goods and services produced in a

year. GNP includes four types of final goods and services, (i) Consumer goods

and services to satisfy the immediate wants of the people (ii) gross private

domestic investment on capital goods consisting of fixed capital formation,

residential constructions and inventories of finished and unfinished goods,

(iii) goods and services produced by government and (ir) net export of goods

and services'

GNP = government production

+ private output

Net National Product (NNP)

The second concept is Net

National Product. The capital goods like machinery wear out as a result of

continuous use. This is called depreciation. This is also called National

income at market prices. Hence NNP = GNP - depreciation.

National Income at factor

cost

National income at factor

cost denotes the sum of all incomes earner by the factors. GNP at factor cost

is the sum of the money value of the income produced by and accruing to the

various factors of production in one year in a country. It includes all items

of GNP less indirect tax. GNP at market price is always more than GNP at factor

cost as GNP at factor cost is the income which the factors of production

receive in return for their service alone.

National income at factor

cost = net national product - indirect taxes + subsidies.

Personal Income (PI)

Personal income is the sum

of all incomes received by all individuals during a given year. Some incomes

such as Social security contribution are not received by individuals; similarly

some incomes such as transfer payments are not currently earned, for example

Old Age Pension. Therefore,

Personal income = national income - social

security contribution - Corporate income taxes - undistributed corporate profit

+ transfer payment.

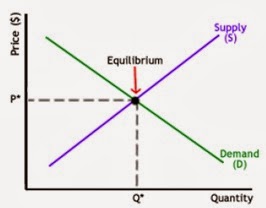

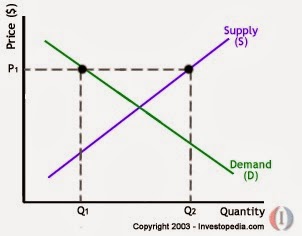

When supply and demand are

equal (i.e. when the supply function and demand function intersect) the economy

is said to be at equilibrium. At this point, the allocation of goods is at its

most efficient because the amount of goods being supplied is exactly the same

as the amount of goods being demanded.

Thus, everyone

(individuals, firms, or countries) is satisfied with the current economic

condition. At the given price, suppliers are selling all the goods that they

have produced and consumers are getting all the goods that they are demanding.

As you can see on the chart, equilibrium

occurs at the intersection of the demand and supply curve, which indicates no a

locative inefficiency. At this point, the price of the goods will be P*and

the quantity will be Q*. These figures are referred to as equilibrium

price and quantity. In the real market place equilibrium can only ever be

reached in theory, so the prices of goods and services are constantly changing

in relation to fluctuations in demand and supply.

Studies of the linkage

between foreign direct investment and development have produced con-fusing and

sometimes contradictory results. Some have shown that foreign direct investment

(FDI) spurs economic growth in the host countries; others show no such effect.

Some find spill-over benefits to the host economy—that is, benefits not

appropriated by investors or in the form of superior wages—while others do not

discern these benefits.

For years, it has been

unclear whether developing countries benefit from devoting substantial

resources to attracting FDI. A government authority in a developing country

might, for example, grant a subsidy to a foreign-invested project if it

believed that the project would produce positive externalities or spillovers.

These could include managerial and worker training, technological learning that

is transferred outside the firm, an increase in supplier efficiency, and

demonstration effects through which the success of one investor persuades

others to invest in the host country. Yet it has proved extremely difficult to

measure such effects.

FDI that is integrated into

the global supply network of parent multinationals tends to be particularly

potent for host country development, while FDI oriented toward protected

domestic markets and hampered by joint venture and domestic content

requirements is not beneficial.

FDI produces different

results in different host countries, the economist offers guidance to

policymakers in both developing and developed countries on ways to ensure that

FDI aids rather than impedes development:

In countries with protected

and distorted economies, FDI is harmful to economic welfare.

Where there is little FDI,

the harm is little. Where FDI is large, however, the adverse effect on economic

welfare is also large. Conversely, in countries with low barriers to trade and

few restrictions on operations, foreign firms can increase the efficiency of

existing economic activity and introduce new activities with strongly favorable

effects on host country development. Consequently, host governments should

adopt open trade and investment policies.

Developing country hosts

should prohibit domestic content, joint venture, or technology sharing

requirements on foreign investment.

Such requirements neither

increase the efficiency of local producers nor produce host country growth. To

the contrary, such provisions interrupt intrafirm trade, which is a potent

source of host country growth, and lead to inefficient production processes,

outdated technology, and waste of host country resources.

Host countries should avoid

competing to give the best tax incentives to foreign investors.

Available resources for

promoting investment are better spent on improving local infrastructure, the

supply of information to investors, and education and training that benefits

foreign and local firms alike.

Developed countries should

back only FDI that promotes the economic welfare of developing country hosts.

Most national political risk insurance

agencies do not screen projects to eliminate those that require trade

protection. Such FDI hurts rather than helps hosts countries. Neither are

taxpayers in developed countries served by FDI projects that lower developing

country welfare and impede trade expansion. Thus these agencies should assess

the degree to which an FDI project promotes host country welfare as a criterion

for agreeing to insure it.

Opportunity cost is the

cost of any activity measured in terms of the value of the next best

alternative that is not chosen. It is the sacrifice related to the second best

choice available to someone, or group, who has picked among several mutually

exclusive choices.

The opportunity cost is a

key concept in economics, and has been described as expressing "the basic

relationship between scarcity and choice".

Example: The

difference in return between a chosen investment and one that is necessarily

passed up. Say you invest in a stock and it returns a paltry 2% over the year.

In placing your money in the stock, you gave up the opportunity of another

investment - say, a risk-free government bond yielding 6%. In this situation,

your opportunity costs are 4% (6% - 2%).

Scarcity is the fundamental economic problem that arises because

people have unlimited wants but resources are limited. Because of scarcity,

various economic decisions must be made to allocate resources efficiently.

Scarcity states that society has

insufficient productive resources to fulfill all human wants and needs.

Alternatively, scarcity implies that not all of society's goals can be pursued

at the same time; trade-offs are made of one good against others. In an

influential 1932 essay, Lionel Robbins defined economics as "the science

which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means

which have alternative uses."

Cross Price Elasticity of

Demand refers to the percentage change in the quantity demanded of a given

product due to the percentage change in the price of another

"related" product. If all prices are allowed to vary, the quantity

demanded of product X is dependent not only on its own price (see elasticity of

demand) but upon the prices of other products as well. The concept of cross

price elasticity of demand is used to classify whether or not products are

"substitutes" or "complements". It is also used in market

definition to group products that are likely to compete with one another.

If an increase in the price

of product Y results in an increase in the quantity demanded of X (while the

price of X is held constant), then products X and Y are viewed as being

substitutes. For example, such may be the case of electricity vs. natural gas

used in home heating or consumption of pork vs. beef. The cross price

elasticity measure is a positive number varying from zero (no substitutes) to

any positive number. Generally speaking, a number exceeding two would indicate

the relevant products being "close" substitutes.

If the increase in price of Y results in a

decrease in the quantity demanded of product X (while the price of X is held

constant), then the products X and Y are considered complements. Such may be

the case with shoes and shoe laces.

The ability of a firm (or

group of firms) to raise and maintain price above the level that would prevail

under competition is referred to as market or monopoly power. The exercise of

market power leads to reduced output and loss of economic welfare.

Although a precise economic definition of

market power can be put forward, the actual measurement of market power is not

straightforward. One approach that has been suggested is the Lerner Index,

i.e., the extent to which price exceeds marginal cost. However, since marginal

cost is not easy to measure empirically, an alternative is to substitute

average variable cost. Another approach is to measure the price elasticity of

demand facing an individual firm since it is related to the firm’s price-cost

(profit) margin and its ability to increase price. However, this measure is

also difficult to compute. The actual or potential exercise of market power is

used to determine whether or not substantial lessening of competition exists or

is likely to occur.

The quantity demanded of a

particular product depends not only on its own price and on the price of other

related products, but also on other factors such as income. The purchases of

certain commodities may be particularly sensitive to changes in nominal and

real income. The concept of income elasticity of demand therefore measures the

percentage change in quantity demanded of a given product due to a percentage

change in income.

The measures of income elasticity of demand

may be either positive or negative numbers and these have been used to classify

products into "normal" or "inferior goods" or into

"necessities" or "luxuries". If as a result of an increase

in income the quantity demanded of a particular product decreases, it would be

classified as an "inferior" good. The opposite would be the case of a

"normal" good. Margarine has in past studies been found to have a negative

income elasticity of demand indicating that as family income increases, its

consumption decreases possibly due to substitution of butter.

Price discrimination occurs

when customers in different market segments are charged different prices for

the same good or service, for reasons unrelated to costs. Price discrimination

is effective only if customers cannot profitably re-sell the goods or services

to other customers. Price discrimination can take many forms, including setting

different prices for different age groups, different geographical locations,

and different types of users (such as residential vs. commercial users of

electricity).

Where sub-markets can be

identified and segmented then it can be shown that firms will find it

profitable to set higher prices in markets where demand is less elastic. This

can result in higher total output, a pro-competitive effect.

Price discrimination can

also have anti-competitive consequences. For example, dominant firms may lower

prices in particular markets in order to eliminate vigorous local competitors.

However, there is considerable debate as to whether price discrimination is

really a means of restricting competition.

Price discrimination is also relevant in

regulated industries where it is common to charge different prices at different

time periods (peak load pricing) or to charge lower prices for high volume

users (block pricing).

Public goods are those

which cannot be provided to one group of consumers, without being provided to

any other consumers who desire them. Thus they are “non-excludable.” Examples

include radio and television broadcasts, the services of a lighthouse, national

security, and a clean environment. Private markets typically under invest in

the provision of public goods, since it’s very difficult to collect revenue

from their consumers.

More broadly, public goods can refer to any goods

or services provided by government as a result of an inability of the private

sector to supply those products in acceptable quantity, quality, or

accessibility.

Gross

domestic product (GDP) is the market

value of all final goods and services

produced within a country in a given period of time. GDP per capita is

often considered an indicator of a country's standard of living. GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It

includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments

and exports less imports that occur within a country.

The short formula of GDP

calculating-

GDP

= C + G + I + NX

Where:

"C" is

equal to all private consumption, or consumer spending, in a nation's economy

"G" is the sum

of government spending

"I" is the sum

of all the country's businesses spending on capital

"NX" is the nation's total net

exports, calculated as total exports minus total imports. (NX = Exports -

Imports)

Nostro and Vostro account normally uses in the foreign exchange

transactions of the banks or during currency settlement.

Nostro Account means the overseas account which is held by the

domestic bank in the foreign bank or with the own foreign branch of the bank.

For example the account held by Bangladesh Bank with bank of America in New

York is a Nostro account of the Bangladesh Bank.

Vostro Account means the account which is held by a foreign bank

with a local bank, so if bank of America maintains an account with Bangladesh

Bank it will be a vostro account for Bangladesh Bank.

It is a great point that

the account which is Nostro for one bank is Vostro for another so when

Bangladesh Bank opens a Nostro account with Bank of America, it is a Vostro

account for them and vice versa.

Sunk costs are costs which,

once committed, cannot be recovered. Sunk costs arise because some activities

require specialized assets that cannot readily be diverted to other uses.

Second-hand markets for such assets are therefore limited. Sunk costs are

always fixed costs, but not all fixed costs are sunk.

Examples of sunk costs are

investments in equipment which can only produce a specific product, the

development of products for specific customers, advertising expenditures and

R&D expenditures. In general, these are firm-specific assets.

The absence of sunk costs is critical for the

existence of contestable markets. When sunk costs are present, firms face a

barrier to exit. Free and costless exit is necessary for contestability. Sunk

costs also lead to barriers to entry. Their existence increases an

incumbents’commitment to the market and may signal a willingness to respond

aggressively to entry.

A joint venture is an

association of firms or individuals formed to undertake a specific business

project. It is similar to a partnership, but limited to a specific project

(such as producing a specific product or doing research in a specific area).

Joint ventures can become

an issue for competition policy when they are established by competing firms.

Joint ventures are usually justified on the grounds that the specific project

is risky and requires large amounts of capital. Thus, joint ventures are common

in resource extraction industries where capital costs are high and where the

possibility of failure is also high. Joint ventures are now becoming more

prevalent in the development of new technologies.

In terms of competition policy, the problem

is to weigh the potential reduction in competition against the potential

benefits of pooling risks, sharing capital costs and diffusing knowledge. At

present there is considerable debate in many countries over the degree to which

research joint ventures should be subject to competition law.

The general term for the assignment of

property rights through patents, copyrights and trademarks. These property

rights allow the holder to exercise a monopoly on the use of the item for a

specified period. By restricting imitation and duplication, monopoly power is

conferred, but the social costs of monopoly power may be offset by the social

benefits of higher levels of creative activity encouraged by the monopoly

earnings.

A special type of vertical

relationship between two firms usually referred to as the

"franchisor" and "franchisee". The two firms generally

establish a contractual relationship where the franchisor sells a proven

product, trademark or business method and ancillary services to the individual

franchisee in return for a stream of royalties and other payments. The

contractual relationship may cover such matters as product prices, advertising,

location, type of distribution outlets, geographic area, etc. Franchise